Jason Franz is the founding executive director and chief curator of Manifest, a creative research gallery & drawing center located in Cincinnati, Ohio

|

Can you share with us a memory or two of first having recognized your passion for the arts?

I remember when I was five or six years old people would ask me what I was going to be when I grew up. My answer was always ‘an artist’. I don’t know why that was my answer. Neither my parents, nor any of my family, were artists, although many of my ancestors had been German craftsmen of one sort or another (cabinet maker, woodcarver, machinist, and the like). I remember loving to draw, and often created worlds on paper within which my imagination could run free.

At some point I was asked the question again, and my answer was the same, but with a twist—that I wanted to be an artist, but I couldn’t be. This was because, as I understood it in that very early formative stage, artists in schools had to take turns modeling nude for each other, and there was no way this modest little boy was going to have anyone seeing him naked, let alone drawing pictures of him. So that was it, the conundrum that somehow turned about and shaped my life.

In looking back I savor the irony in this story. Not only did I study life-drawing in college, I also went on to teach it, co-founded and now lead an organization with a studio program centered on the practice, and my own exhibited work is now primarily life drawing. I’m happy to report that in college I held firm to the red line I would not cross, (thankfully co-modeling is not part of a student’s course participation credit).

In high school I was an introvert. I guess I was some form of art-nerd-computer-geek—a relatively normal shy kid of the early 80’s. By this I mean I excelled in college-prep classes and could relate to the kids I knew were so much smarter and more confident than I, but also felt most at home in the art rooms or dabbling with computer programming. I was not a very sociable teenager. In the end, I did well enough to graduate ranked 10th in my class and earned a few academic awards and recognitions, in addition to those for my art. As a very unworldly naïve boy I was still determined, and encouraged by my father, to go to college (and be the first in my family to do so). I wrestled with choices as a junior and senior in high school for what to study in college. Art was my passion, but I performed well in math and English too. Some teachers wanted me to consider a discipline that would take advantage of my skills in these areas, something like Architecture or Engineering. And there was the usual consideration of the perception (or reality?) that one can’t make a living being an artist, so why spend money, going in debt for college trying to become one? I credit my dad, as conservative and old-school as he was, for urging me to follow my heart. In the end, I entered the Art Academy of Cincinnati at 17 with the intention of majoring in Graphic Design (a creative yet practical compromise, I thought). I will never forget my trigonometry teacher’s disappointment in my decision, and took this as a validation of both my path and the respect of someone I in-turn respected.

It was probably near the end of my freshman year that I determined I could not be happy working for someone else’s ideas, on demand. I craved pure drawing and making images too much. It was my ideas I wanted to explore, not someone else’s. So I changed my intended major to Illustration (still a compromise as a bridge between the two extremes). By sometime in my sophomore year—whenever it was that we needed to declare a final major—I was all in for Painting (and Drawing, and Printmaking, and Sculpture).

Yet another irony is that now, as the director of an 18 year old nonprofit arts organization I co-founded, not only do I use and practice my skills and understanding of visual art every day, (I’m saturated by it!) I also use my skills in math and writing, logic and discipline, and graphic design and illustration.

|

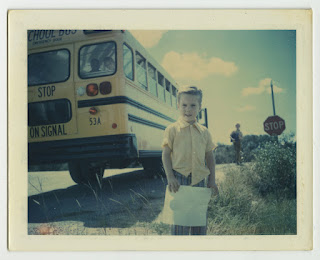

| Circa 1972- "Arriving home from school with the drawing I wanted to show my parents and grandparents." |

What was the catalyst for founding Manifest Gallery?

This could really be a book-length answer, so I’ll cut to the point. If I had to put my finger on just one ‘catalyst’ it was the stage of my career and the state of my academic appointment in the particular environment I was in at the time that did the catalyzing. But it was only by virtue of many many other factors aligning that this energy was able to be realized. These other factors included my own past experiences (as a young artist, college student, museum exhibit designer, practicing artist, professor, and participant in society), along with the students in my courses, my co-founders’ zeal for the ideas we shared, the state of the community we were in, and the combined ‘YES!’ the three of us and many others contributed to the decision to launch.

Another way to look at answering this question is from the outside, and to say the growing recognition of a confusion in society about visual arts (as echoed by a similar confusion in academia) caused Manifest. Put simply, in my teaching of any form of art I usually start with a key point or premise: that having a sense of taste is different than having a sense of quality, and that all too often people confuse the two, or assume they are one in the same. This may be a goal, but is rarely the case. This leads to confusion, misplaced values, a skewing of the role of visual arts in society, an emphasis on marketed narcissism, and ultimately to the decay of the profession of ‘artist’—often exacerbated by the very people who claim to hold that title. This is at least the germ of the reason Manifest’s mission is centered on championing ‘quality’ in visual art. And it is admittedly as much a question as it is a declaration.

Manifest Gallery not only holds exhibitions, but also serves as an outlet for various other programs and projects. How do you find the time to oversee such an extensive organization?

There is never enough time.

(To be clear, Manifest’s full name has always been Manifest Creative Research Gallery and Drawing Center—two halves made up of four quadrants.) Our four programs (exhibits, studio programs, artist residency, and book press) have evolved organically over nearly two decades making Manifest much like a Museum, Library, School, Church, and Gymnasium, all for the visual arts. We’ve been patient, steadfast, and resilient. Slow growth and change is generally wise. It allows for adjustments without breaking anything (too much). It builds trust and reliance with the public. Achievements and ‘quality’ add up, and value increases exponentially. Rather than getting bored and changing in order to remain entertained, we focus on the structure of our organization, its mission, and our interactions with the people who participate.

It is not without a truly heroic staff, supportive board, and many volunteers and supporters, that Manifest came about and continues towards the start of its third decade. But our appearance as an ‘extensive organization’ is a flattering illusion generated by our rigor, structure, and commitment. In truth, Manifest is small by design, with only six paid staff (not including contracted teachers and volunteers), and only two of the staff are full time. I say again, they are heroic. They believe in Manifest’s mission. That’s how we do it.

Which kinds of responses do you wish to evoke in both the public and the artist, through the diverse works that you showcase?

Regarding Manifest’s exhibits we like to say our job is not to sell art, but to sell an experience—for free. So the last thing we want is for the public to think of art as a commodity, or of the gallery as a store for art. We don’t want most of them thinking about ‘cost’. Instead we want them thinking about value—of their experience, the work’s content, the artists’ efforts, and so on. This is not to say we aren’t thrilled if a patron or museum chooses to buy an available work from one of our exhibits—it’s a win-win-win. But this is not our mission.

Referring to earlier answers, we design our exhibits with overall quality in mind (quality of arrangement, relationships, thematic pertinence, craftsmanship, etc.). By this I mean that a jury-approved pool of high quality works is then assembled into a high quality exhibition. If we’ve done our jobs, not only are the works individually appreciated, the whole is too. And in successful art and design the whole is greater than the sum of its parts. In this way, a person may feel the intention and ‘wholeness’ within a gallery experience as a positive force, even while the work included may not be to their taste.

In the end an exhibit designer and installer’s job is to hide their own efforts so that the viewer and the art can have their moment, an encounter in the wild if you will. Maybe the best response comes from someone who says, “I can’t put my finger on it, but I just love these exhibits. Something made me stay and look longer at work I would not have thought I’d want to spend time with, and I kept coming back for more…”

The artists we meet who visit the gallery for their receptions, often from as far away as the west coast, consistently say that in their circles the name Manifest means a lot, and that being in a Manifest show is seen as an achievement they’re proud of and their peers applaud. This has happened enough times over the years that we are starting to believe it, that Manifest’s reputation is solid, and our efforts are valued nationally. A deeper response is when we hear that an artist’s participation in a Manifest show or publication has led directly to further success, perhaps because a curator, commercial gallery, or a museum follows us in search of new talent, or patrons collect our books in hopes of finding new art to acquire and ultimately develop a relationship with an artist we’ve exposed. Whether it's exhibitors, resident artists, or regional participants in our studio program, knowing we’re making a difference in our fellow artists’ lives, now and in the future, is central to confirming we’re on target in fulfilling our mission. So I suppose evoking sincere validation from our peers for whom we work so hard is a goal. We want them to approve of our effort.

What do you love most about running this organization?

For me it has become my life-work, my ‘masterpiece’ not in the sense of a high achievement in history, but in the sense of the work of my life personally, both as an artist and as a citizen. (I also say this with full acknowledgement that it is really our masterpiece, because it is the product of many passionate people giving much towards making it happen. I just happen to be one of the least common denominators throughout Manifest’s history, and have the awesome privilege of steering the ship).

Collaboration. In the way we jury blind, and anonymously, letting a system of input steer the outcomes rather than curatorial or juror ego and ‘identity branding’ shaping the product of our mission.

Connecting. I’ve worked with SO MANY artists from all around the world, I feel like I’ve made small but permanent connections in any major city and so many smaller places. (We’re at 3,636 and counting). This is despite the fact that I work fairly hands-off, and remotely from the artists, communicating mostly through email. Likewise, I see artists connecting with each other because of their shared path-crossings in a Manifest exhibit, and this warms my heart and tells me what we’re doing is good on so many levels.

Proof. Hearing from artists far away from here how much Manifest means to them, and others in their circles. We started this, and do what we do, with a gut sense that it’s important and right. But as with any art endeavor, one always has a shadow of doubt. Getting unsolicited validation from the people who would know best is so energizing, and fulfilling especially when the work feels hard.

Celebrating excellence. On a selfish level, or perhaps because of my nature as a teacher, I always want to see better art in the world. Manifest is designed to fulfill this indulgence to an exquisite extreme. The books we’ve produced, over 30 major publications and 74 full-color exhibit catalogs, capture this in a small but very meaningful way. Taking a step back and paging through them after all this time recently made me realize how tangible all that work (mine, my staff’s, and the artists’) has been. (Not enough people see the books. manifestgallery.org/manifestpress

Sharing this with my family. Brigid, my wife, is co-founder. While I’ve been immersed in it as Director for half of my adult life, Brigid has remained involved both on the Board of Directors and as my partner in life. In both capacities she’s played a critical role in the evolution, progress, and success of Manifest and this often goes unseen because it is, as often as not, at the DNA level. But without her there’d be no Manifest.

And that brings me to one of the last things I love the most… Alexandra, our daughter. She was conceived when Manifest was conceived, at around the same time we signed the lease on the space that would become Manifest Gallery (mid-2004). She was born three weeks after our public debut of our first exhibits which was on January 7, 2005. She has attended almost every opening reception at the gallery (149 and counting) and has seen every exhibit both as it has formed in the curatorial/design phase, and in person in the gallery. She first drew from the live nude model when she was three, alongside professional and student artists in our Open Figure Life Drawing program. Alexandra has taken a college degree’s worth of professionally instructed studio classes at Manifest’s Drawing Center with some of the best artists in the country (and some from outside the country), and soaked up every bit of it. She has been teaching her own private studio lessons for youth and early teens for Manifest for the past three years. And her work is exceptional, revealing the power and influence being surrounded by quality-vetted art (and dialog about it) can have on a young person developing as an artist. As Manifest moves towards its gallery’s 17th anniversary of opening to the public and Alexandra moves towards her 17th birthday, I realize the organization is the child-becoming-adult, and the organization and the child are as twins. The processes a parent must go through as their child transitions into adulthood are, I suspect, paralleled by those a founder of a nonprofit arts organization must go through as the organization matures. It’s scary. Exciting. Inspiring. Uncertain. Motivating. And life-framing.

What are some of the challenges that you face?

The answers are mostly boring… the same as any nonprofit: funding, space, time, staffing support, atrophy in society… COVID…

A major challenge is caused by our longevity. If you last long enough, you inevitably encounter one problem-challenge or another. A good example is the lease-term existence (operating in facilities that are leased rather than owned). Even with an unprecedented and generously arranged long-term lease, we are now faced with having contributed to the successful turnaround of our neighborhood—and face the threats that come with that financial reality. I suspect that in most cases a vibrant small nonprofit can cause far more ‘positive growth’ in a community than it gets back in reciprocal support. Therefore it is unsustainable as an institution, even if the community deserves and needs such a valuable resource in its midst. At the same time, funders often focus on ‘impact’ (using art as a blunt instrument and a means to an end), or a point-A to point-B short-term solution to some perceived need—all too often at some expense to the arts and artists if not society at large. They forget about point-C, and what happens to the impactor once they’ve successfully made the impact and now are buffeted by the reverberation. Usually there is no support allowance for picking up those pieces. We’re left to do it ourselves. But we believe that art should be valued as so much more than fertilizer.

Bias. As a small artist-founded and artist-run nonprofit organization we do what we do at great personal sacrifice, significant efforts to give back so much more than is given, and to make the whole a valuable part of the larger arts ecosystem—one that benefits even the artists who don’t have work selected for exhibition or who don’t participate directly. Yet some artists apply a bias to Manifest (and our fellow organizations), assuming we are the same as the disreputable venues or programs they may have had bad experiences with out in the world—including those which are not nonprofit, governed by a board, run by artists, etc. It saddens me to see such closed mindedness in fellow artists, as few as they may be. It reveals a pattern of thought that probably pervades other aspects of life, decision making, and their careers, and is harmful on both a small and large scale. Part of this is life as it is. Part of it is our challenge to do the work and cut through the misunderstanding by doing a better job communicating our values, rationale, and mission. It’s an ever changing landscape we continue to move through.

Do you have plans for Manifest Gallery and Drawing Center beyond what it is today?

The real question is does it have plans for me!

But yes, Manifest is always becoming.

We, staff and board of directors, are routinely in dialog about thinking ahead five or ten years. Our goal is to cement Manifest’s legacy as a valued and important Cincinnati-based visual arts nonprofit institution and secure it in a permanent home that will continue to bring the vibrancy of learning, experiencing, practicing, and sharing visual art from near and far, magnified tenfold over what we’re able to do now in what must be considered our two one-mile apart ‘temporary’ facilities.

So, survival and progress. That’s the plan.

No comments:

Post a Comment